In defense of Mickey Mousing

This is my contribution to Damian Arlyn’s Film Music Blog-a-Thon at Windmills of My Mind. ___________________________________________________________

A catchy negative term can do a lot of damage. As far as film criticism is concerned, just consider the massive abuse of a phrase like “style over substance“, a knee-jerk “yeah, right” to instantly smother a filmmaker’s poetic license, or the buzzword of the moment: “torture porn.” In more or less the same category falls the catchphrase Mickey Mousing.

Mickey Mousing is the standard description for film music that directly mimics the action onscreen. You know, just like the old Disney shorts: Goofy falls flat on his face–TOOT!–a tuba honks. A classic example is the ending of the original King Kong, in which the music is crescendoed in such a way as to suit Kong’s motions in climbing the Empire State Building.

In criticial and educational circles, Mickey Mousing is often looked down upon. The general consensus is that it’s lazy, cheap and old-fashioned for a soundtrack to ape the visuals. And yet many Hollywood maestros frequently make use of the technique: Danny Elfman (Beetlejuice, The Simpsons), Hans Zimmer (Spirit, Pirates of the Caribbean) and the late Jerry Goldsmith (Gremlins, Total Recall).

The opposite of Mickey Mousing takes place when a piece of music complements the images to establish a general mood or theme. This is usually called underscoring. Contemporary underscorers are Cliff Martinez (Traffic, Solaris), Michael Nyman (The Piano, Gattaca), Gustavo Santaolalla (Brokeback Mountain, Babel), Thomas Newman (American Beauty, Little Children), Alexandre Desplat (Birth, Syriana) and Philip Glass (Candyman, The Hours). These guys rarely emphasize what’s already on the screen, and needless to say, I appreciate their work as much as the next cinephile.

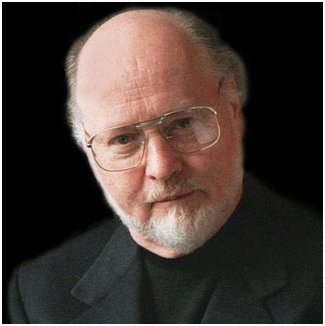

The king of Mickey Mousing?

With no one questioning the merits of underscoring, why exactly deserves Mickey Mousing such a bad rap? What seems to bug people the most is that it wears its intentions on its sleeve. Mickey Mousing tells the audience explicitly what to look for, how to empathize, and when to laugh, cry or shiver. It takes the frontal assault, whereas most critical minds prefer a soundtrack to blend into the background and leave room for personal reflection. Frankly, some of us don’t like to be blatantly manipulated.

Even respectable directors like Sidney Lumet (in his excellent book Making Movies) and John Carpenter (in his director’s commentary on the Prince of Darkness DVD) have openly expressed their disdain for Mickey Mousing. The latter jokingly crowned John Williams the king of Mickey Mousing. In the same breath, Carpenter claimed that Bernard Hermann was the quintessential underscore composer, with Vertigo being an honorable example.

Fair enough. A bombastic music cue like The Imperial March (you know the one: “TAAA! TAAA! TAAA! TAA-TADAA! TAA-TADAA!”) leaves little room for ambiguity. It practically screams out to the audience: Beware! Something Sinister, Totalitarian and Oppressive has entered the room! And honestly, isn’t that exactly what makes the tune so irresistable to begin with? When a hard-breathing Darth Vader is about to wipe Rebellion ass, do we expect anything less than military drums and pumping brass? Of course not! A gentle woodwinds motif just wouldn’t cut it…

![]()

Click to hear a sample of The Imperial March

By the same token, what’s not to love about Hans Zimmer in prime fighting shape, or a rousing Danny Elfman score? And before you start to think that Mickey Mousing doesn’t leave room for subtlety: Take another look at the prom scene in Carrie, in which Pino Donaggio‘s music Mickey-Mouses in perfect harmony with Brian De Palma’s visual orchestrations to bring you to the edge of your seat in anticipation for the bucket of blood to fall.

In fact, I’d even argue that Vertigo‘s soundtrack, which Carpenter embraces as a full-blooded piece of underscoring, incorporates quite a bit of Mickey Mousing. There’s no doubt that Herrmann’s haunting score is layered and full of conflicting emotions, but it sounds fittingly lyrical when Scottie and Madeleine share a passionate kiss, and appropriately disturbing when Scottie’s fear of heights comes into play. And wasn’t it Hermann who wrote Mickey Mousing history by syncing shrieking strings to the fatal stabs of a killer’s knife in the world’s most famous shower scene? When a composer drums up a frenetic, percussive score to support a thrilling car chase, or lays an elegiac theme over a melancholic tableau, his or her technique isn’t that far removed from Mickey Mousing. The music still follows and punctuates the visuals–only the beats are longer.

Sometimes film music is supposed to take a back seat or provide its own commentary on what happens in the picture. Sometimes film music needs to work in tandem with the visuals to help the viewer relate with the characters or a given situation. Both approaches are legitimate. You can spend the rest of your life arguing wether Thomas Newman (Finding Nemo) or Scott Bradley (Tom & Jerry) wrote the superior soundtrack, and I’ll say: Isn’t it great that we don’t have to make these either/or choices? We can have both to enjoy!

___________________________________________________________

RELATED:

“Our minds may focus on what there is to see, how we experience the view is often heard.”

Sound as Vision: Riding The Blind Giant

Marvelous, Peet. Simply marvelous.

You have written an excellent defense of “mickey mousing.” I admit that I have never liked the term and have always found that approach to film scoring quite enjoyable and effective. Yet I can also appreciate “underscoring” (particularly in documentaries) and I think you’re right in that we don’t have to choose one over the other. We can enjoy both. Sometimes a composer will actually employ both styles in the same film. You mention Hermann’s work for Vertigo and that’s an excellent example. Some sequences are indeed “underscored,” but watch the scenes where Stewart tries to get up the stairs or he rushes to rescue Novak from her drop into the bay and tell me that’s not “mickey mousing.”

Thank you for your contribution to the blog-a-thon, Peet. It is much appreciated. 🙂

Another aspect of Herrman’s wonderful Vertigo score that would fit into your thesis is when Scottie and Madeleine enter the church while Scottie is initially pursuing her. Immediately when Scottie enters we hear a traditional organ hymn, but then we see the church is empty and no organ is visible (if I remember correctly). Hitchcock/Herrman kind of pull the rug out on us, for a second making us believe that the sound is originating “in” the movie, but in fact it’s just another part of the soundtrack — and the hymn ends just as Scottie exits.

You’re welcome, Damian! I loved to contribute and I’m trying to keep up with all the entries to your wonderful Blog-a-Thon. Congrats so far!

Adam: Interesting observation. I’d have to check that, since it’s been a while since I played the DVD.

I’ve been to comment on this great post for days now…As I sorta kinda maye almost alluded to in my own contribution to the ‘thon, I think it all boils down to what’s appropriate and doesn’t overpower a scene. Too much music, Mickey Mouse or not, can really ruin a quiet dialogue scene…but if someone’s being stabbed to death all of a sudden and out of nowhere, by all means make with the shrieking violins!

Pingback: Forward to Yesterday - Bob Westal Classic Film, Movie, & Television Blog

Just call me “Boob.”

You’re absolutely right, Bob. Too much music can kill the drama, and some scenes work best with no music at all. Whatever fits the moment. Thanks for linking!

Oh, and that’s “Gelderblom” with one “O.” I won’t hold that against you. 😉

I would say there’s nothing wrong with Mickey Mousing, so long as it’s used sparingly. The problem with Hans Zimmer is that most often these days his score compliments every scene in the movie. I love “Batman Begins”, but the music is constant, hardly leaving a moment for silence. But then sometimes Zimmer’s score works, like in Pirates or Gladiator, it can be quite rousing.

Kurosawa talks about music that contradicts what’s happening on screen. The best example that comes to mind probably isn’t the best, but if you recall “Face/Off”, when one of the big shootouts occurs, the young girl is listening to Somewhere Over the Rainbow. That would be Mousing in reverse…perhaps my example is a little blatant, but it gets the point across.

Thomas Newman happens to be one of my current favorites. You overlook Michael Kamen (dead now) but brilliant while he was around.

Thank you for talking about scoring in the first place. It’s something many reviewers over look when they write because most often a great movie will have an appropriately great score, but it’s never mentioned. I try my best to bring it into the light every chance I get.

Actually, *all* music scoring is called “underscoring.” That’s why the Emmy for musical scoring in a TV series is given for best “Dramatic Underscore.”

I recognise this is a very late comment, but I only just discovered this post. Though Spider-Man 3 wasn’t great, the moment it was really ruined for me was at the end when someone says “I forgive you”. In a split second I thought, this could be a poignant moment if the score doesn’t inturrept, but no sooner did I think it than the emotions-dictating music intruded right on cue.

What do you call the opposite of Mickey-Mousing, that is, when the film is edited to match the music, as Leone did in Once Upon a Time in the West? In the final showdown, for example, Harmonica appears on screen, and Frank drops his coat, are both accompanied by new significant developments in the score.

Yet at the same time, the “operatic” score, complete with choir, reflects the emotion of the scene but does not match the lack of displayed emotion by the characters. I think that’s another favorite device of Hermann, for example the ferry ride in De Palma’s Obsession: visually a mundane scene but the rousing score reflects Cliff Robertson’s hidden anxiety.

Pingback: the music of sound » Film Music rant#1

Hey! I like every use of the buzzword “torture porn” … if it can push Tarantino and Cronenberg out of business, but I digress.

Excellent article. My feelings exactly. One little-studied source of the mickey-mousing vs. underscoring debate is the natural antagonism between French and German music (of which “serious” British music is a subset). Composers like Herrmann were naturally attracted by British and German intellectual, profound and dour composers while others (like Viennese Max Steiner) also incorporated freely the French influence of verve, sprightliness, immediacy, frankness, sentimentality, invention, grotesquerie and melody for melody’s sake. Herrmann wasn’t a brilliant melodist, but he was very good at setting moods with the smallest number of elements possible (verging on minimalism). Mickey-mousing, on the other hand, requires a lot more hard work (and notes!) than underscoring, as well as a perfect mastery of counterpoint, fugal and melodic development (sometimes ad absurdum) and rythmic complexities. In other words, it embraces the whole artisan tradition of the XIXth Century and is shameless in its paraphrasing, pastiche and referencing of an “old-fashioned” tradition. (What tradition isn’t?) There wouldn’t be any mickey-mousing without Meyerbeer, Massenet, Chabrier, Bizet, Offenbach, Dukas, Saint-Saëns et al. And there wouldn’t be any underscoring without Wagner, Mahler et al. Even if Wagner’s use of leitmotiv is just the intellectual, upmarket, “snooty” use of good ol’ mickey-mousing. I personnally enjoy the recent restorations of great Disney scores like “Snow White”, “Pinocchio” and “Bambi” which are little miracles of mickey-mousing – and complexity – and a great tribute to the legacy and spirit of French music (pre-Stravinski) in general.

Excellent comments, Benoit! Thanks for sharing this information with us.

You’re welcome, Peet. If you can just tolerate a bit of “esprit de l’escalier”, I would like to add: There are very few French symphonies just as there are very few German ballets (the idea of which almost boggles the mind). The Russians of course were influenced by both traditions and picked and chose as they went along, whereas the French pillaged merrily in the Italian heritage. Some even go so far as to say the French stole everything from the Italians, except ballet. I mention this because “mickey-mousing” is closely related to the idea of ballet music (musical accompaniment to silent action scenes). The whole subject should also be correlated to what Michael Powell called the perfectly “composed film”: a film where the action and the musical accompaniment are perfectly planned and choreographed to create the ultimate operatic poignancy. Ironic that Hitchcock’s famous musical theme comes from Gounod’s “Funeral March of a Marionette”, isn’t it?

Kurosawa talks about music that contradicts what’s happening on screen. The best example that comes to mind probably isn’t the best, but if you recall “Face/Offâ€, when one of the big shootouts occurs, the young girl is listening to Somewhere Over the Rainbow. That would be Mousing in reverse…perhaps my example is a little blatant, but it gets the point across.