The end of cinema is (only the) beginning

All this talk about the uncertain future of film criticism seems to run parallel to another hot topic among worried cinephiles: the decline of cinema. The two are connected, obviously, and although I’m definitely in the minority on this one, I’m optimistic about the fates of both.

In a contribution to Andy Horbal’s pretty damn amazing film criticism Blog-a-Thon (how much evidence for the improving health of film criticism do you need?), Annie Frisbie at Zoom In Online articulated a collective concern in a fine post called Film is about to disappear over the historical horizon:

Cinema has always meant reverence, the hush of a dark theater (sans cell phones), the flicker of light on my face almost tangible, waiting for the dream to continue. It seems to me that the digital age has taken the magic out of movies. (…)

This year brought Half Nelson and Little Miss Sunshine, but it also marks a year when I saw fewer movies in the theater than I did when I was in college in the suburbs without a car. I find this depressing. I’m losing the plot. I need a miracle.

In my celluloid fantasia Nighthawks – a fictional essay in which New York City is overtaken by movie characters as diverse as Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver), Barbarella, Alvy Singer (Annie Hall), Vincent & Jules (Pulp Fiction) and Marge Gunderson (Fargo) – a cute little mass-murdering rodent by the name of Mickey Mouse voiced a similar sentiment:

People don’t care anymore. They used to look up to us in the dark, in awe of that eye-enveloping screen, absorbed in the magic of the moment, hanging on to every word we uttered. Now they’re just killing time, flipping channels, skipping chapters, moving us around with game controllers, navigating content, shuffling context, downloading us to tiny portable displays they command with their thumbs…

At that moment, Dressed to Kill‘s Kate Miller briefly interrupts Mickey to remark:

If they’re doing all of these things, doesn’t that mean they still care about us, only differently?

Mickey, however, won’t listen:

You don’t mind being reduced to mobile wallpaper? I mean, where’s the allure in that? Face it, to the modern consumer we’re a hip accessory at best. An excuse for further browsing without sense of destination. It’s sad when you think about it. They watch but they don’t see. Deliverance has become a dirty word, attention spans are shrinking by the minute. Viewers expect to be transported, but they won’t let us take over the wheel. So they keep driving in circles, blissfully unaware of the fact that, without surrender, there is no journey.

Too many cinephiles grumble about like Mickey; few are as open-minded as Kate. To complain about the rapid decay of cinema with a sense of melancholy is to put the lid on an era. That way of thinking, understandable as it may be, is a bit of an insult to the fine films that are made today. (For those of you snorting in the back: In case you haven’t noticed, there’s a Golden Age of Asian cinema happening right now. Genre films, art house, animation… the works.)

It’s rare for a medium to die. People have predicted the end of radio since the introduction of television, and radio’s still here. The medium even branched out to podcasts, streaming channels and audio books. Likewise, cinema isn’t dying–it’s evolving. The real question is, into what?

Annie Frisbie’s post payed tribute to a classic 1999 essay by Godfrey Cheshire entitled The Death of Film, The Decay of Cinema. Cheshire’s towering article envisioned a future where movies would still be made, only they would “increasingly be like Titanic, splashy spectacles made for a global 12-year-old whose main education comes from you-know-what,” lacking “nuances of tenderness and tragedy, of profound inwardness and chivalrous discretion, and of the individual artist’s very personal way of envisioning the world.” With a frame of reference restricted to blockbuster fare and a certain brand of Oscar contender, there’s plenty of truth to Cheshire’s vision, but a wider perpective reveals how much his prediction has dated.

Just look at the massive popularity of viral videos and audio-visual mashups at YouTube, MySpace and iFilm, of video podcasts, of DVD, Home Theatre and online rental services like Netflix, of devices like the video-iPod, the PlayStation Portable, PDAs, laptops, camera phones and software like BitTorrent and Final Cut Pro. A quickly expanding part of cinema is making a gradual shift from a collective, linear experience to a private, interactive one. Yes, the quality of user-generated content is still far from consistent (to put it mildly), and oh yes, all these ultra-flexible digital networks and continually updated interfaces can easily lead to pointless “browsing without sense of destination,” but I can imagine no better antidote against Cheshire’s “CGI blockbusterdom” doom scenario than this small-screen revolution. Who knows, we may be on the verge of a filmmaking Rennaissance. Picture it: A cinema of intimacy… discovery… a quirky perspective unfiltered by authority, corporate investment, analog distribution or popular demand… the bittersweet fruit of obsession and shameless self-indulgence… the mystique of a message shrouded by an ever-fluctuating context, offering audiences the challenge to guess the right questions, rather than the right answers.

If this is the end of cinema – and I’m not convinced it is – it’s only the end of cinema as we know it. Now is a time of transformation. The key to appreciating the change, I believe, is a wise notion of fellow-blogger Girish Shambu: Art is meant for use. That may be your miracle right there, Annie. Go ahead, give it a try. Mickey was right about one thing: Without surrender, there is no journey.

The contrarian fallacy: Armond White vs. the Hipsters

The following article is my contribution to Andy Horbal’s film criticism Blog-A-Thon. Visit No More Marriages! for an up-to-date table of contents.

One is Hip or one is Square (the alternative which each new generation coming into American life is beginning to feel), one is a rebel or one conforms, one is a frontiersman in the Wild West of American night life, or else a Square cell, trapped in the totalitarian tissues of American society, doomed willy-nilly to conform if one is to succeed.

–The White Negro: Superficial reflections on the Hipster (1957) by Norman Mailer

What’s a rebel to do these days? According to the gospel of Armond White, film critic of New York’s premier alternative newspaper the New York Press, the Hip are the new Square. In review after review, White makes it abundantly clear that hipster is the most insulting label he can think of. In fact, it’s his umbrella term for everything he calls smug, glib, trite, obtuse or smart-ass, which by the way he tends to do quite often. Say goodbye to Mailer’s “psychopathic brilliance” of Hip, quivering with “the knowledge that new kinds of victories increase one’s power for new kinds of perception.” Enter White’s endless tirades against the mindless evil of hipster mentality eroding pop culture, embodied by the likes of Quentin Tarantino, Todd Haynes, Richard Linklater, Christopher Nolan, Peter “the hipster’s Spielberg” Jackson and any critic empty-headed enough to praise them.

Armond White’s style of criticism couldn’t be more different than that of his NY Press colleague, Matt Zoller Seitz. If this were the X-Men universe, we’d be talking about the militant Magneto (a mutant terrorist with a serious superiority complex, eternally at war with humanity) versus the noble Professor X (a peaceful telepath who seeks coexistence of human- and mutantkind by means of education). While White keeps his ivory tower firmly locked, Seitz has plugged into the blogosphere and founded his very own Xavier’s Institute with The House Next Door, a school of gifted youngsters that embraces respectful discourse and mutual understanding. The militant spends most of his time criticizing his peers, the telepath surrounds himself with them.

White more or less articulated his view of film criticism in Slate’s Movie Club, where he answered Salon‘s Stephanie Zacharek as follows:

As for the “art” of criticism: No amount of fancy wordplay can excuse the destructive effect of praising offal like Before Sunset. (That’s not a personal attack, it’s a defense against the injury of bad criticism and poor taste.) I don’t read criticism for style (or jokes). I want information, erudition, judgment, and good taste. Too many snake-hipped word-slingers don’t know what they’re talking about—especially in this era of bloggers and pundits. That’s why a hack like Michael Mann gets canonized while a sterling pro and politically aware artist such as Walter Hill is marginalized. Let me be more blunt: I am not the least bit interested in reading the opinions of people who don’t know what they’re talking about. There, I’ve said it.

Indeed, he said it. It’s one thing to challenge the opinion of others, it’s another to proclaim absolutes in the name of Good Taste. A true provocateur doesn’t hamper by discouraging thought, but stimulates others to think differently. Why is it that some critics judge like punishing Old Testament Gods when their function is not to damn or win souls, but to sharpen minds? A critic’s pen should serve as a whetstone, not a sledgehammer.

Contrarians like Armond White aim to prove that there is something inherently wrong with the limited world view of another, while their actual concern is to establish a few limits of their own. By consistently taking the opposite stand, they reveal themselves as just as much a fashion victim as the hipsters they so despise. While the latter slavishly embrace the latest trend, the former just as predictably oppose it. Both the hipster and the contrarian poses attempt to overthrow a shared enemy: the dominance of mass culture.

Which, in this day and age, begs the question: What mass culture? With the millions of niche markets currently out there, what’s left of it, really? By the same token: Is there still a single definition of hip? In a time where one icon means everything to one subculture and entirely nothing to the next, what is this nonconformist rebelling against?

It’s like everybody’s hip now. It’s exhausting. There’s no discovery. It’s not original.

Those words were spoken by futurist Faith Popcorn way back in October 2005. That was when the L.A. Times published an article entitled Fads are so yesterday, which announced that coolhunting itself, even the whole notion of “cool,” was just a trend. In January this year, Maclean’s columnist Andrew Potter took this observation to the next level:

(The) mass-media ecosystem has disappeared, replaced by the rip/mix/burn culture of the Internet with its blogs and podcasts, in which there is no longer any distinction between producers and consumers. The really interesting bit is not, as Faith Popcorn would have it, that everyone is cool; it’s that no one is. Trends appear as nothing more than brief consumerist shivers, passé the moment they appear (…)

Aha! So, should we be mourning the end of trends? The kids certainly aren’t, argues Potter:

Having never really experienced the tyranny of mass society, they don’t feel any great urge to stand against it. That is why they adopted the word “random” as their preferred term of approbation. The people who have a problem with the death of cool are aging hippies and other stubborn counterculturalists who remain attached to the idea of a mass society and its right-wing agenda of cultural conformity.

Clear enough. But that leaves us with one final mystery to solve: If cool’s out, what is in? Potter explains:

The prevailing aesthetic is not cool, but quirky, dominated by unpredictable and idiosyncratic mash-ups of cultural elements that bear no meaningful relationship to one another. Appreciating the anti-logic of quirk is the only way to navigate the movies of Wes Anderson (Jeff Goldblum in an “I’m a Pepper” T-shirt!) …

Hold on. Quirky? Idiosyncratic? Wes Anderson? Help me out here–who denounced Syriana in favor of Sahara and Transporter 2? Who called the universally acclaimed Nicole Kidman only “moderately talented”? Which critic belongs to the whopping 8% of idiosyncratics that Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat (2006) couldn’t get to smile?

Wouldn’t you know it… Armond White is a hipster.

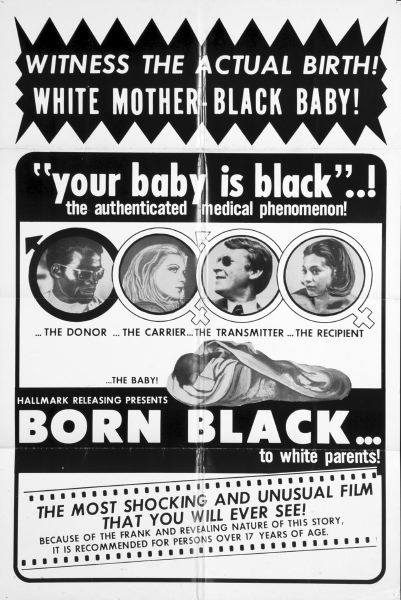

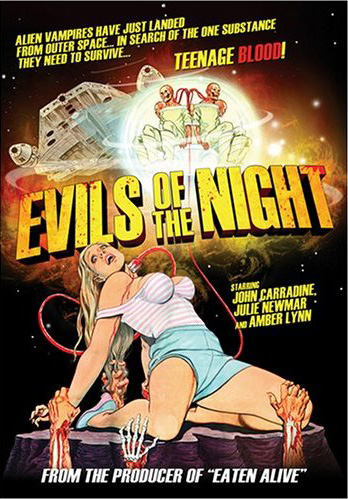

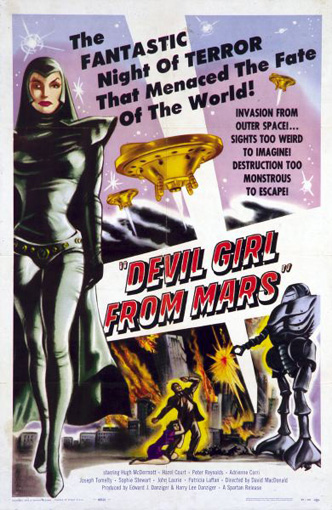

Movies doomed to never top their poster #2

You need to love this, don’t you?

The hard evidence, courtesy of DVD Talk:

Take a good look at the DVD cover art for Evils of the Night (which is taken from the film’s original poster) and you see the definition of an exploitation film. We see a buxom blonde whose blood is being drained from her body by tubes as skeletal hands reach for her and a quartet of skeleton-head aliens look on (as the cousin of the Millennium Falcon flies past). Of those things, only the buxom blonde appears in the film. Don’t be fooled by the trashy goodness that this movie promises. This movie gives bad movies a bad name. (…)

The “aliens” are simply actors in silver outfits, with the females wearing crazy shoes. The “spaceship” is just a disco light ball being lowered through the trees. (…)

The bulk of the movie takes place at night (hence the title) and for the most part, it’s nearly impossible to tell what’s going on. (…)

Most films of this ilk typically fall into the “so bad they’re good” realm where one can perform a Mystery Science Theater 3000-like commentary to the movie. Evils of the Night is so pointless, boring, and difficult to see that its ponderous nature will scare off even the hardest fan of trash cinema.

Sigh…

David Lynch Folds Space: mind-origami at 24LiesASecond

I realize we’re not exactly prolific at 24LiesASecond (The House Next Door we ain’t!), but when we do publish something, we try to make it worth the wait. Today is a joyful day…

When Bob Cumbow, author of Once upon a Time: The Films of Sergio Leone and Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter, emailed me a few months ago with a new idea for a 24LiesASecond essay, tantalizingly titled “David Lynch Folds Space,” I went nuts! Gone was my contributing-editor cool, and up jumped a drooling fanboy.

As a teenager – I was thirteen at the time – I found Lynch’s Dune (1984) as puzzling as anyone who’d never read Frank Herbert’s novel. Nonetheless, the concept of “travel without moving” as explained by Princess Irulan in her opening monologue, always made perfect sense to me. Why cross all those light-years from galaxy to galaxy when you can simply fold the distance? You can’t, of course… but the idea just seemed so obvious, so right!

Bob’s plan to apply the very same concept to David Lynch’s work was a stroke of genius (Mel Brooks didn’t call Lynch the Jimmy Stewart from Mars for nothing!) and we had lots of fun speculating on the subject in our email correspondence.

An excerpt from David Lynch Folds Space: Because He Is the Kwisatz Haderach!:

Folding space consists in bringing two spatial points together by collapsing the space between them, thus eliminating the need to move from one to the other. Dune’s “explanation†of travel without movement, of the folding of space, is a sly announcement of not only the vision but the technique that David Lynch brings to the screenwriter’s and film director’s art.

So early in Lynch’s career, in only his third feature film, we have a pseudo-scientific articulation of the artist’s unique way of seeing the world, and of remaking it. For folding space is a near-perfect metaphor for the way David Lynch makes movies.

For a mind-bending trip to the epicentre of Lynchian logic, read Bob’s whole article at 24LiesASecond. If you like it, don’t hesitate to drop a note in its dedicated thread at the 24Lies Article Feedback forum, or comment on it here.

Come wander with me

The spirit of René Magritte haunts this mesmerizing commercial for the Dutch insurance company RVS. If I ever find out who directed this, I’ll plan an assassination to take over his/her job. The song Come Wander With Me is from Jeff Alexander, sung by Bonnie Beecher, lifted from an old Twilight Zone episode. Very nice.

______________________________________________________

Most of you will have seen the cut-down version by now (without the clown): The latest Sony Bravia ad, directed by one of my favorites, Jonathan Glazer, who once more shows a penchant for channeling Stanley Kubrick. Like the previous Bravia film, this was all shot in-camera, as the following behind-the-scenes documentary will show you.

______________________________________________________

And just because I think you guys deserve it: Here’s a a taste of Mike Figgis’s arty sleazefest for lingerie house Agent Provocateur. The four-part series Dreams of Miss X was shot in night vision and stars Kate Moss in very little clothes… Hello? Are you still here?

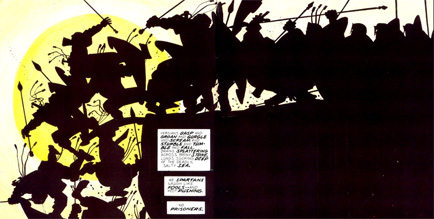

Anticipating 300: Pixels will blot out the sun!

When I read Frank Miller’s 300 a few years ago, I very much doubted if this graphic novel could ever be successfully adapted to film. Not because the story was too vast and complex to survive the translation, in a way Neil Gaiman’s intricate Sandman saga is; or too outrageously blasphemous like Preacher by Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon. No, simply because of Miller’s virtuoso use of extreme comic stylization within a historical framework.

Nevermind that we’re talking about the ancient battle of Thermopylae, in which King Leonidas and his personal guard of 300 Spartans held off an army of one million (give or take) Persian warriors in a narrow gorge. Faithful reconstruction my ass! This is Frank Miller’s tall, mythical take on the historical event, existing in a universe all of its own. The swollen hyperboles, the ferocious violence, the supreme machismo and glorious heroism–it all worked to great effect on the page. Any attempt to approach this material in a less stylized manner, I figured back then, would make it seem utterly ridiculous.

That was before Robert Rodriguez pushed the envelope of comic book faithfulness with his film version of Sin City (2005). Doubt turned into hope: Here was a movie that dared to stray from the medium’s inherent photorealism with expressive lighting, a digitally controlled color palette and (most importantly) all-CGI-backgrounds. The method proved so flexible that it even allowed the makers to match each shot of the film to every drawn panel in the comic. From the moment it was announced, I realized it was a wise move to follow a similar route for 300 (2007). And judging from his surprisingly solid remake of Dawn of the Dead (2004), Zack Snyder is just the man to pull it off.

Last month my hopes were rewarded by an awe-inspiring teaser trailer. Apart from the stunning imagery (watch this comic-to-screen-comparison to get a sense of how much Snyder sticks to Miller’s vision), this trailer excels at what the comic medium is incapable of showing: actual movement. Anything is possible now… Hear my inner geek roar!

Children of Men

I’ve just come back from seeing Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men. What a marvelous film! Don’t expect a full review here (others are much better at that than I am). Instead, let me just say this:

Plausibles are complaining about the movie’s “hard-to-swallow” premise, being: humanity on the brink of extinction because of an unexplained crisis of infertility. They have no idea what they’ve just witnessed. Children of Men may very well carry the most relevant and potent metaphor of our times and manages to do it justice.

Cuarón has entered the Big League, that’s for sure. One instantly classic long take inside a driving car combines total chaos with laser precision film-making, bringing to mind the Spielberg of Munich and War of the Worlds (2005). I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more successful blend of gritty realism and stylized storytelling.

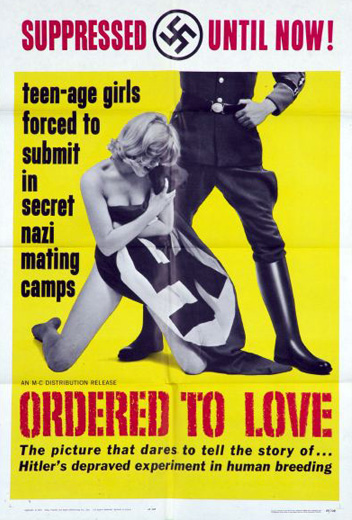

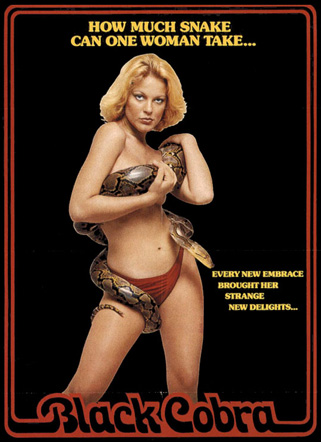

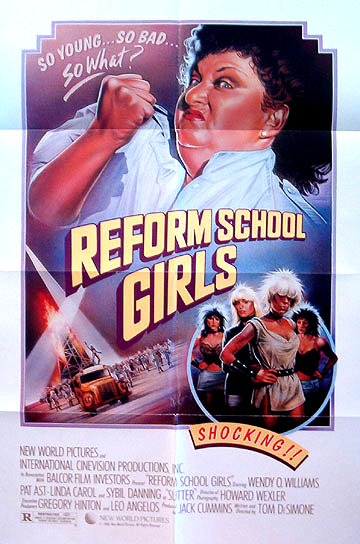

Movies doomed to never top their poster #1

Not convinced? Click here and scroll all the way down the page to see a short video with the hard evidence.

I hate to be right…

Movies doomed to never top their posters #1

Not convinced? Click here and scroll all the way down the page to see a short video with the hard evidence.

I hate to be right…

Keith Haring paints himself

I’m not an unconditional admirer of Annie Leibowitz‘s high-concept photography (A portrait of the Blues Brothers? Oh, I know: Let’s paint their faces blue… Genius!) and I’m not as crazy about Keith Haring as I used to be. But Leibowitz’s portrait of a body-painted Haring is without a doubt sublime.

At home I have a framed poster of that photograph. It’s on the wall of our lavatory, where it frequently startles unsuspecting guests. The picture is printed in full-color – despite the additional costs that such a decision entails – just so you can barely make out Haring’s pink skin underneath the black-and-white paint camouflaging his body.

Annie did Keith quite a favor with that portrait. With just one click of her camera, she helped a fellow artist reach the highest obtainable. In that fraction of a second, Keith Haring became one with his art.

It was the gift of a lifetime. And as early as Haring may have passed away, he will rest in peace forever.

We are betrayed by brains that are too small

Illustration by Anthony Hare

After reading this interview at Times Online in which Christiane Kubrick, widow of Stanley, sets the record straight once and for all, it’s easy to see why her marriage with Stanley lasted 42 years. What a wise and fascinating woman.

If there is a theme that runs throughout Stanley’s films it involves people making enormous mistakes even though we’re aware that the choices they make are probably wrong. We are betrayed by brains that are too small. Our frustration and wickedness possibly derives from that fact.

Source: The ScreenGrab.

So what’s with all the evil bunny suits?

The phenomenon can no longer stay unnoticed: What is it with the recent prevalence of sinister-looking bunny suits in indie films? I see evil man-rodents everywhere! Don’t you?

Spot the difference: Donnie Darko & Starfish Hotel

The movie that unofficially kicked off this subliminal trend may have been Gummo (1997), which featured a creepy kid with large bunny ears. Three years later, audiences were haunted by Gal Dove’s long-eared ghost from the past in Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast (2000). Next up was spirit animal Frank in the cult-favorite Donnie Darko (2001), and then “The Mysterious Bunny Man” in Cabin Fever (2002) reared its ugly head. Meanwhile, David Lynch – never one to waste a good surreal image – treated the visitors of his website to a stage with a family in rabbit costumes in his curious sitcom Rabbits (2002). Much to the confusion of Geoffrey Macnab, Lynch appears to have incorporated similar sequences in his latest feature film Inland Empire (2006), offering no explanation whatsoever. And if the aforementioned titles convinced you that we’re dealing with a typical Anglo-Saxon phenomenon, the recent release of the Japanese supernatural detective thriller Starfish Hotel (2006) and this South-Korean poster for Chan-Wook Park’s upcoming film I’m A Cyborg will no doubt change your mind.

Left: Gummo, right: Sexy Beast

But that’s not all. Something similar seems to be going on in the realm of music videos. Just watch Pink’s Just Like A Pill, Christina Aguilera’s Dirrty, or Do You Realize by The Flaming Lips. Distressingly enough, the evil-bunny-suit fever is currently spreading out over the Internet, infecting esoteric cinephiles in the blogosphere (source: Greencine Daily‘s David Hudson).

How are we to take this odd phenomenon? Is it a metoo effect? Plain old ripping off? In an interview held by fellow-blogger Ross Ruediger at The Rued Morgue, Firecracker director Steve Balderson discourages the plagiarism accusation:

Say I’m inspired by a surrealist piece of art where there’s a man wearing a giant stuffed-animal costume. Let’s say I wanted to incorporate that idea into my movie. Well, some might say I stole the idea from Donnie Darko, which features a person dressed in a stuffed-animal costume. Or, others might suggest I’m trying to be David Lynch because he did the same thing with Naomi Watts dressed in a bunny outfit.

By focusing on things like that, people will fail to recognize what it is that I’ve done. Never mind I’ve never seen the David Lynch scene with Naomi Watts. Never mind that my inspiration had nothing to do with Donnie Darko. What I think would be more interesting is if one would ask the question: What drives an artist to arrive at a similar conclusion? Where did the choice originate to put someone in a stuffed-animal costume? By answering that question, and appreciating what is on screen all in and of itself, the viewer will get more out of it.

Amen to that. So, leaving aside Balderson’s fictional example of that “surrealist piece of art,” what is the real origin of cinema’s ongoing fascination for people in stuffed-animal costumes? Are we facing the painful aftereffects of a generation of filmmakers traumatized over Monty Python and the Holy Grail? Probably not… Although some people have pointed out eerie similarities between Donnie Darko and the film Harvey (1950), in which James Stewart as Elwood P. Dowd has an imaginary six foot rabbit friend, much like Donnie has Frank. Writer-director Richard Kelly, however, claims he has never seen the Jimmy Stewart film (nevermind the Bruce Willis remake) and that his Frank was inspired by the novel Watership Down.

Harvey: Early blueprint for

the current man-rodent craze?

Eli Roth – who insists that his screenplay for Cabin Fever was written in 1995, long before Donnie Darko came out – names a completely different source of inspiration in an interview with Rebecca Murray:

ROTH: The Bunny Man was very influenced by The Shining. There’s a scene in The Shining where Shelley Duvall’s running around the hotel and she sees these creepy things. There’s a guy in a bear suit who is just really, really, really weird. It always stuck with me as a kid so it’s kind of my little nod to The Shining.

MURRAY: But that was a bear, and this is a bunny. Why the change to a bunny?

ROTH: We just couldn’t find a bear suit. I think that there’s something very evil about a bunny suit.

Cabin Fever

The quote above tells me that, as far as this little investigation is concerned, a focus on direct influences will lead us nowhere. Maybe we should be digging deeper. Perhaps there is something about the image of a person in a rabbit outfit that resonates for these filmmakers on a level even they cannot quite fathom. As unlikely as it may seem, maybe we just need to accept the possibility that evil man-rodents are… in the air.

What’s that, am I being too vague? Well, prepare for a dip into Donnie Darko territory as I indulge myself in a little game of pseudo-scientific free-association.

David Lynch’s Rabbits

With his innovating theory of morphic resonance, the controversial British biologist Rupert Sheldrake proposes that self-organizing systems of all levels of complexity – atoms, molecules, crystals, organelles, cells, tissues, organs, organisms, societies, ecosystems, planetary systems, solar systems, galaxies – are shaped by morphic fields that contain an inherent memory. In the human realm, Jung referred to this as the collective unconscious. The process of morphic resonance takes place when phenomena – particularly biological ones – become more probable the more often they occur, so that growth and behaviour are guided into patterns laid down by previous similar organisms. In other words: much of what we are, think and do is inherited without us realizing it. A constantly updated pool of collective memory binds us even when we’re oceans apart. Seen from this angle, even mental activity and perception can be viewed as habits, and habits are subject to natural selection.

It begs the question: Can a successful creative idea cause a certain thinking pattern to spread and evolve into a habit? When one filmmaker has contemplated the use of a bunny suit for sinister effect, does it become easier for others to arrive at the same cinematic solution by simply tuning into the same wavelength? Call it “creative instinct,” “tapping into the Zeitgeist,” or “divine inspiration,” if you like. Wouldn’t such a theory (Gelderblom’s Hypothesis of Collective Inspiration–bring on the Nobel Prize, baby!) explain the contemporary wave of CGI-animated movies featuring domesticated furry animals heading back to the wild?

Or am I simply behaving like the pattern-seeking animal that I am (to borrow Jim Emerson‘s favorite phrase) and is our unhealthy obsession with evil bunny suits, of all things, God’s idea of a practical joke on humanity? I’ll leave the final words to Richard Kelly’s Donnie and Frank:

DONNIE: Why do you wear that stupid bunny suit?

FRANK: Why are you wearing that stupid man suit?

The screen speaks

No shake of hands

No kiss goodbye

There is no door to my side of the world

Only windows to see through

Cold glass to lay an ear against

Draw the curtain

Watch me dance

I long to show you

You need to see me

The closer you look, the nearer I come

So feast your eyes:

Let my glorious reflection

Paint the blush on your grey face

I am immortal

I am ideal

I am illusion

Surely unreal

Look at me!

______________________________________________________

The above monologue was taken from a screenplay I wrote for an as yet unrealized short film, titled Remote Control.

Sound as vision: Riding the blind giant

Watching a good movie is like falling under a spell. Gradually, without realizing it, you take the limits of the screen for the limits of the world. Everything else is forgotten, your heart opens up and your mind surrenders to the will of the filmmaker. Ninety minutes later you gain consciousness and walk out of the theatre a little different than how you got in. It begs the question: What was it, exactly, that got you this far?

Most people would say it was the gripping story that glued them to the screen, or the suspenseful way it was told. Others would argue their sympathy for the main character drew them in. A few would mention the intoxicating gaze of the camera, the movements, the rhythm, the colors, the shapes. But who would be clear-headed enough to give credit to the invisible? We don’t just watch a movie, after all: we listen, too.

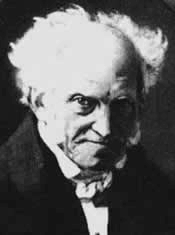

In his central work The World as Will and Representation, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 -1860) compared the human intellect to a lame man who can see, riding on the shoulders of a blind giant. The Mind does not control the Will. The same metaphor applies when you take a look at how people experience and interpret movies. In the filmic universe, our window on the world is framed by the vision of the director, but this vision may not be carried by visuals primarily. If we wouldn’t spend most of our time revering the mighty Image, we might realize the extent to which our thoughts and feelings are guided by a blind giant called Sound.

Why do critics and academics refer to cinema as a “visual†medium even though that word only covers half of the definition? When every Special Edition DVD comes loaded with a wealth of behind-the-scenes material, highlighting every detail from location scouting to CGI effects–how come only, say, 0.01 percent of these extras go into the craft of sound recording, sound mixing or sound design? Show off hands: Which of you cinephiles can name five movies supervised by the Godfather of Film Sound, Walter Murch, without checking the man’s IMDb page?

The fact that audio in motion pictures is often overlooked can be largely explained by its abstract nature. You can point out the lipstick on a husband’s collar, or spot the bad guy holding a gun in the crowd, you can freeze a frame and enlarge it, but it’s hard to put a finger on the disturbing effect of a faintly detectable bass drone accompanying a series of seemingly ordinary shots. Images are frontal and direct, triggering a primarily cerebral response; sound tends to work on a subconscious, more emotional level.

To clarify the difference between how we perceive the two, the aforementioned Walter Murch came up with a brilliant analogy based on the sideways position of the ears. It goes something like this: While we – the audience – are answering the front door by looking at the screen before us, sound sneaks in through the windows, the back door and the floorboards, encompassing us in a 360° spherical field. As it resides in the shadows, its subliminal presence becomes a conditional force, affecting the things we’re consciously aware of. According to Murch, The strange thing is that you take the emotional treatment that sound is giving, and you allow that to actually change how you see the image. You see a different image when it has been emotionally conditioned by the sound.

That’s right, sound’s a sneaky bastard! Our minds may focus on what there is to see, how we experience the view is often heard. Anyone who’s ever spent a good deal of time experimenting in the editing suite will back this up. In my capacity as a filmmaker and editor, I’ve witnessed and creatively exploited this phenomenon time and again. To radically change the emotional impact of a sequence of shots, I have often simply replaced a piece of music in post production. Oddly enough, replacing the shots themselves never results in something quite as drastic. Just how fundamentally a soundtrack can alter our perception becomes clear in the following mock trailer edited by Robert Ryang, which re-imagines Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining as a sparkling family comedy. Hear: a single music cue is all it takes to switch around the mood and snap the viewer into an appropriate state of mind.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/w/shining?v=1J9ufqCoqyo&search=shining]

One of the finest recent uses of conceptual sound design, however, can be heard in the trailer for the upcoming Todd Field film Little Children. This one and a half minute long miracle was created by Mark Woolen and Associates, a trailer company that was briefed to come up with something without music, elaborate dialogue or story. The result is nothing short of breathtaking and one can only hope that the film is able live up to its promotion (so far, opinions are divided). One thing’s for sure: Unless you’ve ever been tied to the railroad tracks, the sound of a train horn never sounded more foreboding…

Black Book in primary colors: Verhoeven’s back!

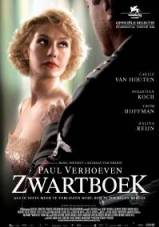

Between invisible apes strapped to operating tables and pretty Jewish girls who dye their pubic hair in extreme close-up, the choice is easy… Welcome home, Paul Verhoeven! Zwartboek, Verhoeven’s first Dutch film in over twenty years (if you include 1985’s Euro-pudding Flesh & Blood), is the work of a director doing exactly what he wants, and nothing else. So it’s good, then? Oh yes. I’d go so far to say it’s Verhoeven’s best.

Paul Verhoeven has never been afraid of the Big Gesture. It’s what he’s all about. Zwartboek is no exception. In a recent interview, actor Thom Hoffman (who starred in De Vierde Man as well as Zwartboek) compared Verhoeven to the abstract expressionist painter Karel Appel, known for his motto “I paint like a barbarian in these barbarian times.” The comparison makes sense. Verhoeven’s style is the cinematic equivalent of CoBrA action painting: exploding with robust imagery, primary color schemes and violent brushwork. But don’t be fooled–this Dutch Master’s broad strokes often work together to paint a finely nuanced picture. Behind Zwartboek‘s brawny sense of adventure is a cautiously calibrated morality play.

Not that it should come as a complete surprise. In the case of Zwartboek, Verhoeven and regular screenwrite Gerard Soeteman (Turks Fruit, Soldaat van Oranje, De Vierde Man) took twenty years to do their homework and refine their script until it snapped, crackled and popped, referencing a rough total of 800 documents, articles and books on the Dutch resistance. They based their film on real events and concocted a fictional storyline to glue those facts together.

Thematically, the film is rooted in Verhoeven’s experiences of growing up during WWII. Back then, the parents of one of his best buddies were members of the NSB – a Nationalist party that sympathized with the Nazis – convincing him that there were endless shades of grey between black and white. Verhoeven set out to make a picture in which no single character is purely innocent or strictly evil (although I believe he permitted himself one or two out-and-out villains). This in itself is not a radical philosophy – especially not in these trivial times – but it’s a truthful one. Zwartboek leaves you with the impression that the Liberation never came, that human atrocity lives on forever and people are not to be trusted… But hell, life’s sure worth the ride!

All people behind the scenes worked miracles to make 17 million euros look like 70 million dollars. They had a hard time to raise money for this picture in Europe, but on the bright side Verhoeven gained access to an unbelievable pool of available acting talent. The lovely Carice van Houten as Rachel/Ellis, especially, is radiant in her leading role and Verhoeven quite rightly calls her the most talented actress he’s ever worked with. Here’s a heroine that modern audiences need to see more of: strong, down-to-earth and witty. When this brave young woman finally breaks, you’d have to be a cold-hearted stump of a being to not break along with her.

The same quality level can be found on every level of the production. I take back my initial doubts about director of photography Carl Walter Lindenlaub (Independence Day). His crisp lighting style is a good match with Verhoeven’s larger-than-life sensitivity. Lindenlaub wisely avoided shooting in black and white, sepia-tone or using a bleach-bypass process and based Zwartboek‘s look on German color films from the 1940s instead. (Whether Lindenlaub succeeded in his approximation is not for me to judge–it’s been a while since I saw one.) Anne Dudley’s score sounds like a cross between the military marches that Rogier van Otterloo composed for Soldaat van Oranje and Jerry Goldsmith’s eerie-ethereal main theme from Basic Instinct.

Frustratingly enough, the critical reception in the Netherlands doesn’t seem to be very positive. Some things never change. It just shows how good the Dutch are in underestimating their own artists. Until they die, that is.

Production notes

After the principal photography of Zwartboek was completed, I’ve worked with a couple of its crew members on two of my own projects (the camera dolly we used was still marked with a “Carl Walter Lindenlaub” sticker). They told me that Verhoeven prefers to shoot in sequence to keep his actors in the moment, which meant that the lighting constantly needed adjusting as soon as the director decided to switch over to a reverse angle. And the man never, ever shoots a master. It’s in his contract, simply to avoid impatient producers going: “We’ve got the scene, I just saw it. Move on!”

Now listen to this: Apparently, Sharon Stone called Verhoeven on the set of Zwartboek directly after the release of Basic Instinct 2. When she asked him if he liked it, Verhoeven exclaimed in his clunky Dutch accent: “But Sharon, you look TERRRIBLE! How could they’ve DONE this to you!” Tact was never his thing. Thank heavens for that.

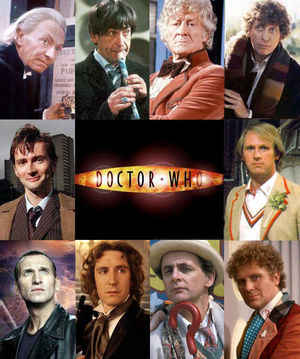

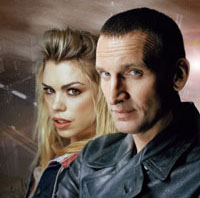

Help, I’m turning into a Whovian!

The far future. Humanity faces the dawn of an intergalactic war as Earth is invaded by a giant fleet of evil mutants. A Time Lord from the planet Gallifrey plans a pulse of energy that will decimate the invaders, but may kill off the human race along with it. His trusted companion, possibly the only person who could put an end to the unfolding cosmic tragedy, is stranded oceans of time away. Twenty minutes to Armageddon… and the fucking screen goes to black.

I have a problem. A big one. Last weekend, the last episode of the new Doctor Who series (starring Christopher Eccleston as the 9th Doctor) was aired on Dutch television. I made sure to program my DVD-recorder in order not to miss it, and now it turns out that only half of the episode has been recorded. Apparently, the hard drive was full! My eight-year-old son Rasmus, who’s become a die-hard Whovian over the course of a single season, is not amused. I don’t blame him–I nearly can’t get over it myself.

I’ve never been a Trekkie, I’ve just about lost all interest in that famous galaxy far, far away, but there’s no way I can resist the Whoniverse! Doctor Who is swiftly becoming a new obsession of mine. It’s gotten to the point that I ordered a pack of Doctor Who Top Trump cards over the Internet, along with two fully illustrated guides documenting every foe, robot, alien and monster the Doctor has ever encountered. How did it come to this?

As a young kid, the classic BBC series with Tom Baker freaked me out. The electronic theme music was enough to chill me to the bone (I still think it outdoes Mission: Impossible in terms of contagiousness), let alone the eerie planetary landscapes and baddies made out of egg cartons. Back then, I was unaware of the Doctor’s rich history in television and I soon lost track of the British sci-fi phenomenon altogether (mind you, we’re talking about the longest running sci-fi series ever, with 23 seasons shown from 1963 all the way through to 2006). But the new series, produced by Russel T Davies, has finally shown me the Righteous Path…

So what hooked me? In spite of some pretty cool creature designs and CGI-effects, the production value of the new Doctor Who is still nothing to write home about, and the quality of the individual episodes is far from consistent. What really got me excited, though, is the the unexpected depths of its profound silliness, the amazing flexibility of the Doctor’s quirky universe and the speculative audacity of his mind-bending escapades. This series, much like its protagonist, doesn’t avoid uncharted territories. It embraces change and finds shades of grey in the most black-and-white of concepts.

Take the Doctor’s most notorious nemesis: the Dalek. Simply put, the Daleks are the most ruthless race in all creation. Indeed, you can’t get any more black-and-white than that, but here it comes: While they appear to be armoured robots, their casing is in fact the survival chamber for a hideously mutated alien life form. Mutated how? By one thousand years of exposure to chemical and biological warfare, for starters… Followed by a little tweaking courtesy of the crippled alien scientist Davros, who morphed what was left of his species into lethal creatures in travel machines, devoid of any emotion save hate–without pity, compassion or remorse. The implanted Dalek survival tactic is simple yet effective: Exterminate all life forms other than your own.

Watching the episode Dalek, I started out chuckling over the title character’s ridiculously impractical pepper pot design, before being completely caught up in the suspense of the story. By the end, the poor lonely creature trapped inside its tank-like mechanical cage, lost in its own destructive thinking pattern, had almost driven me to tears. Quite a feat! This is the kind of nuanced imaginative fiction that you’d love to see handled on a Hollywood budget, but seldom will.

For an impression of the first new series, check out the YouTube clip below. (In the UK, David Tennant as the 10th Doctor has already picked up where Eccleston left off.) To see two ultraviolent reenactments by my two boys and me, click here and here. I know: I’m beyond redemption…

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLiXUbCuaTY]

Categories

- Blog (119)

- Cartoons (29)

- Embarrassing Movie Posters (15)

- Movies Doomed To Never Top Their Poster (2)

- Projects (36)

- Screening Room (1)

Greatest Hits

- Boys like Peet are not afraid of wolves

- Faces I love

- In defense of Mickey Mousing

- On evaluative criticism

- Screening Room: The poor man’s motion control

- Screening Room: Two women on a bench

- Skinny-dipping with Angelina Jolie

- So what’s with all the evil bunny suits?

- Sound as vision: Riding the blind giant

- The contrarian fallacy: Armond White vs. the Hipsters

- The end of cinema is (only the) beginning

- The Five Words Challenge

- The screen speaks

Interviews

Websites & blogs

- Angry Alien Productions

- Cartoon Brew

- David Bordwell & Kristin Thompson

- De Palma à la Mod

- Drawn

- Filmkrant

- Filmmaker Magazine blog

- IndieWire

- Parallax View

- RogerEbert.com

- Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule

- Some Came Running

- The Balloonist

- The Comics Reporter

- The House Next Door

- Thompson on Hollywood

- Trailers From Hell

- Vimeo Staff Picks

Your Photostream

- Instagram Error :Bad Request